Systems: Art

God is a systems artist.

That statement probably doesn't mean that much to you. It means a lot to me. That simple sentence is the foundation for one of the most life-altering realizations I have ever had.

Why? That's a hard question to answer. Ever since I recognized the personal import of this statement a few weeks ago I've been trying to figure out how to explain and communicate what I can see and feel but can't seem to put into words. I've actually been ruminating on this idea for almost four years and, unsurprisingly, it's rather difficult to put four years worth of thoughts into one essay. I'll do my best.

To start, I think it's best to answer a few questions: What is a systems artist? How do you know God is a systems artist? So what?

The term, Systems Artist, describes a small subcategory of artists that originally emerged in the 1960s-ish. Systems artists got their name from their use of systems to create art. In stark contrast to the abstract expressionism (a very emotional form of art) and object-focused art of the time (think Minimalism in which objects are isolated from their surroundings in order to better appreciate the shape, or Photo-realism in which objects are represented with perfect, life-like detail in order to appreciate the shape within its surroundings), systems art was very logical, often mathematical, and based in reason. Furthermore, systems artists was not at all interested in the object, the subject, or the scene. In many cases, the artist wasn't even interested in the end result or "art" that was produced. Rather, the artist was wholly engrossed in the process of creation and discovery.

A systems artist outlines a set of rules and restrictions and follows those rules religiously. Cybernetic systems art involved the use of audio feedback loops that were strung together in a certain way based on predetermined rules much like the "If Then" statements used in computer programming. Process art was a common form of systems art used in painting in which the artist would repeat the same motion over and over (think flicking a paintbrush over a massive canvas repeatedly "just" to watch where the paint falls). Today, those less familiar with art and its history likely label systems artworks as abstract art--seemingly without a subject or purpose. And while it's true that the majority of systems artworks are abstract pieces, there is a lot more to a work of systems art than what is actually represented on the canvas or sculpted into clay.

I was introduced to systems art during my first semester of college and I have been completely enthralled with the art form ever since. I loved how using a system gave the work of art more depth. I loved how easily my appreciation for mathematics and geometry fit into the system. I loved the mental aspect of the art. And I loved the fact that logic and reason (things not often associated with creativity and art) could become something beautiful, unexpected, and creative.

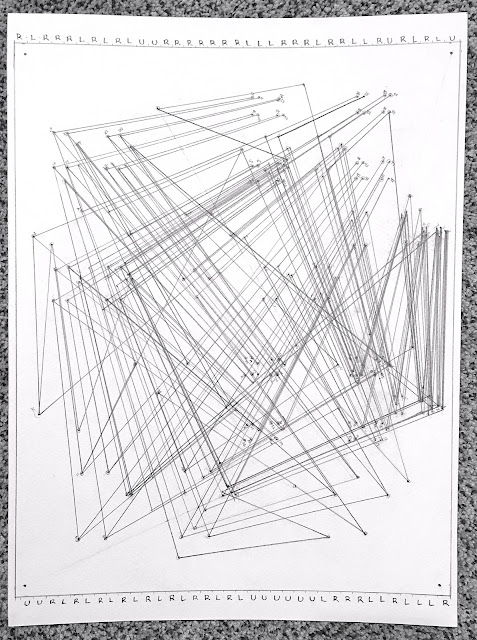

Still don't understand the allure? Let me show you my first work of systems art.

What do you see? Abstraction? No subject? A unique but rather uninteresting conglomeration of lines? The occasional number, star, circle, or eraser mark? I'll admit, just looking at this work of art, I wouldn't be that impressed either. But let me tell you what this is.This is a visual representation--a catalogue--of...my feet. Or rather, the movement of my feet as I tracked them for 30 minutes while staring out the third floor window of the library one day.

Why? I actually don't know. I just needed some form of data to base my system off of and I randomly got curious about my feet. How much did I move them without realizing it? Did I have a nervous habit of bouncing or twitching my feet? If so, did I move one foot more than the other or treat them equally?

Enter Rule #1 of my system: I was not allowed to skew the data or ignore any movement of either foot (no matter if I merely twitched my pinky toe). Nor was I allowed to intentionally stop moving my feet even if I got worried that I'd moved one foot way too many times in a row. I grabbed a piece of paper and started writing R for right foot, L for left foot, and U for when I moved both feet at the same time (super creative, I know). Once I thought I'd collected enough data, I started wondering how I was going to turn this random collection of useless information into something visual.

Enter Rule #2: I was not allowed to erase or alter lines (barring the two times I drew the line far past its mark because I got distracted). There's a part of me that would think this rule would be obvious, but you don't know how hard it is to draw a predetermined line in a predetermined place when you're quite sure that line is going to ruin the entire piece and would rather it didn't exist, or that you could place it where you wanted it.

Enter Rule #3: I would continue on drawing lines until I'd run out of data. I was not allowed to stop before I'd run out just because I thought the piece would look better with fewer lines.

Enter Rules #4+: Mostly just a set of logistics. I like rectangles, so I chose a rectangular shape with 4 points as my basic structure. For each set of data, R, L, or U, I would draw a predetermined number of lines in a predetermined direction. How did I determine that direction? Well, any R would (obviously) mean the next line would go toward the right (I decided top right because why not?). Any L would take the line toward the top left. Any U would make the line split going both toward the right and left upper dots. So as not to make the image too confusing, I decide that each line would be 1/2 the distance from the current line's position to the intended dot. That way, no matter how many times I went in the same direction, I would never reach the dot (except for when I got distracted :). Finally, I realized that if I kept the page oriented the same direction all the time the drawing would get very boring very fast. So, whenever I had multiple of the same set of data in a row (e.g. RRRRR), I would turn the page 90 degrees counterclockwise.

Enter Rule #?: I also didn't erase the identifying marks that I used to keep track of where my current starting point was. The number of U data that I had meant the line eventually split into 42 different lines at one time (though they eventually merged together again), and it was rather difficult to keep track of. So I circled dots, wrote numbers, and placed little stars in important places to help keep everything straight.

After that, it was merely a matter of repeating the same procedure over and over again until I ran out of data.

Now look at the image again. Does the drawing look different at all given the background information? It might not. Still, I can't help looking at this drawing and trying to trace the line back to the starting point, or trying to identify which set of lines correlates with which set of data. I can't help laughing at how ridiculous it is that this random collection of lines is based on the restless movement of feet. I see something different because I understand the history and the process, no matter how ridiculous they are.

I do believe this is a good work of art and it could probably stand up to inspection in a gallery. But the work of art itself is not as important as what I discovered from the process of creating it. I learned that there are moments in art when you think you've ruined a piece. You draw a line and it throws off the balance of the entire work. You want nothing more than the erase that line, but it's too late and not possible. For the next 10 lines you're constantly wondering if its even worth continuing because that line was so disastrously placed. And then somehow, miraculously, after you've added enough lines, balance is restored and the piece looks even better than you could have ever imagined.

I learned that even the smallest details make an enormous difference. I learned not to overlook the little things. The numbers and circles I added to help myself keep track of everything became valuable pieces of the finished product. And something as stupid as wondering how often I moved my feet could become a B-grade work of art.

But, do you want to know what I think is the most amazing thing about systems art? Its the endless, eternal possibilities. Consider. I could collect a new set of data. I could track my feet for another 30 minutes and then follow the exact same system the exact same way and the work of art would turn out completely different. I would never come up with the same image. I could repeat and rework the same system endlessly. And no matter how many times I repeated the same process, I would always--always--create and discover something completely new.

Part 2: Systems: God coming June 19, 2022.

Comments

Post a Comment